- Home

- Richard Monte

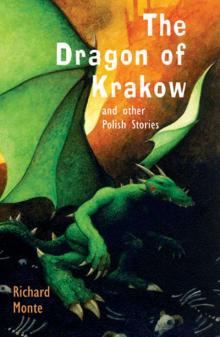

The Dragon of Krakow

The Dragon of Krakow Read online

The Dragon of Krakow

and other Polish Stories

Written by Richard Monte

Illustrated by Paul Hess

The Dragon of Krakow copyright © Frances Lincoln Limited 2008

Text copyright © Richard Monte 2008

Illustrations copyright © Paul Hess 2008

First published in Great Britain and the USA in 2008 by

Frances Lincoln Children’s Books, 4 Torriano Mews,

Torriano Avenue, London NW5 2RZ

www.franceslincoln.com

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electrical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying. In the United Kingdom such licences are issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data available on request

ISBN 978-1-84507-752-5

eBook ISBN 978-1-90766-693-3

Set in Galliard LT

Printed in the United Kingdom

3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

For Malgosia, Anna and Dominick

Contents

Introduction

The Dragon of Krakow

The Amber Queen

The Gingerbread Bees

The Golden Duck of Warsaw

Mountain Man and Oak Tree Man

Neptune and the Naughty Fish

The King who was eaten by Mice

About the stories

Introduction

The stories in this collection prove that there is much more to Poland than the usual picture of a grey land scarred by war and Communism. There are magical tales to be found all over the country – beneath castles and palaces, in towns and cities, in forests and mountains. If you are fortunate enough to travel there and look hard enough, you will find them.

I first started thinking about writing these stories when I was staying in Krakow with my wife nearly ten years ago. We were visiting Wawel Castle, the former home of Poland’s kings in the days when Krakow was the capital city. There was a statue of a dragon outside the palace, and I soon realised that sometimes folklore can be more powerful than history. The legend of the Wawel dragon – or Smok Wawelski, as the Poles refer to him – lives on. There is even a dragon’s den beneath the castle where tourists flock in their thousands to learn about the creature which once lived under Wawel Hill before Krakow was built. So there it was: a strange tale about a dragon which had threatened to destroy this beautiful city at its birth.

The image stayed in my mind, and later my wife retold the tale to me. Whenever we travelled to Poland – to Warsaw, to the Tatra Mountains, to the Baltic Coast and Gdansk, I was on the lookout for more stories. And I found them everywhere. With the help of my wife’s family in Poland, who kindly recalled all those they knew from childhood, a few made their way into this book.

They still strike me as being some of the most unusual folk tales I have ever come across. There are passages as gruesome as anything in the Brothers Grimm, like the king who is eaten by mice as a punishment for his selfish ways. There are humorous episodes, like the two boys who grow as tall as giants and find they can move mountains and pull up enormous forests of oak trees. And there are scenes of great beauty, like the mermaid who lives in an amber palace under the Baltic Sea.

So if you go to Poland, look out for the amber which is sometimes washed up on the Baltic shore. Remember that the reason why Torun gingerbread tastes so good is thanks to the forest bees and their honey – and don’t forget that a dragon once lived in Krakow!

The Dragon of Krakow

A king called Krak decided to build a city at the centre of his kingdom. He travelled widely with his team of advisers looking for a suitable site and eventually settled on a little hill by a river, where trees grew and birds sang.

“What a beautiful place this is!” exclaimed the king. “So peaceful and inspiring. The air is clear, the water is pure – it is the healthiest place I have ever seen!”

A survey was made and Krak’s advisers reported back to him. Only one thing troubled them.

“Your Highness, in our opinion the site you have chosen for your city has everything you need for building houses and churches, and the river will bring in trade. We could begin building your castle on top of the hill tomorrow, but something worries us.”

“And what is that?” asked the king.

“Under the hill there is a cave, and in this cave is a huge, green speckled egg. We cannot identify it and we dare not move it, for fear of harming whatever is inside.”

“Show me!” said Krak, and they took him into the cave. In one of the damp, warm tunnels the king observed the giant egg.

“Don’t worry about it,” he said. “Go ahead and build my castle and my city. We will not disturb the egg. Besides, it could well have been here for thousands of years and may never hatch.”

So his advisers went away and stopped worrying. They brought in the architects and building began. People moved into the city from all over the kingdom. Shopkeepers set up shops – bakers, wine merchants and shoemakers. Everyone was greedy for trade.

The years passed and Krak named his prospering city Krakow. He was a good king, and the people loved him.

Then one day there was a loud C-R-A-C-K.

The king heard the shell of the egg break open. He sent his best men into the tunnels beneath the hill, and half of them returned with the news that a dragon had hatched from the egg. The other half were eaten alive.

“A dragon!” exclaimed Krak. Suddenly the room grew dim and, looking out of his window, he saw the creature flying, its huge wings almost blotting out the sun.

“Good God above!” exclaimed the king. “That tail alone could wipe out the city with one swish! Its mouth is so big, it could grind this castle into little stones with a single bite!”

“And it’s still only a baby, Your Majesty,” said an adviser.

“A baby!” the king gasped.

A day came when he looked out of the window of his castle and saw the damage that had been done to his kingdom. The crystal-blue waters of the river Vistula, which wound its snaky path through the countryside below the hill, were no longer crystal blue, but jet-black and full of ash. The clusters of willow trees drooping over the riverbanks were scorched and the sheep with their white winter coats grazing on the hillside were disappearing quickly.

“The nightingale rarely sings in the woods now,” lamented the king, “and the air is always smoky.”

“Your Highness,” said a counsellor, “we fear that the dragon is growing too fast. When it takes a bath in the Vistula, the river floods. The town is under threat.”

The king sighed gloomily.

“It seems I am at war, and the sight of my kingdom turned into a battleground unsettles my peaceful heart. What am I to do?”

His advisers told him to start training pages to be knights, and to store weapons in his wine cellar.

“There are no armies at my gates waiting to attack my kingdom,” said the king, “yet the jewel in my crown, the beautiful, dazzling, gold and turquoise city of Krakow, with its cobbled streets and wooden churches, with its little green hill and stone castle perched above the river is being attacked” – the king looked out of the window again – “by a dragon!”

At a general meeting, King Krak was informed about the state of his kingdom by a little man reading from a pile of parchment.

“Green fields scorched black.

River full of ash.

Walls of churches burnt and covered in soot.

&

nbsp; Sheep eaten and carcasses picked clean.

Economy in ruins.

No trade.

No livestock for farmers to sell.

Market traders staying indoors.

Fishermen complaining that all the fish in the river

have died.

Army devastated.

Knights’ armour strewn all over the ground.

Swords and shields scattered far and wide.

Dented metal and slaughtered horses everywhere…”

“Anything else?” added the king sarcastically. “The kingdom’s in a terrible state. What can I do? Whenever I walk across the wooden floor, I am reminded at every step of the egg which has hatched beneath my feet. Between the gaps in the floorboards, little puffs of steam keep rising and water vapour fills the rooms of the castle. The walls are beginning to crack as the water cools, trickles down them and collects in pools on the floor. Mould and mildew, green and brown, thick, damp and smelly, has begun to form between the bricks. What am I to do?”

“Do not fear, Your Majesty. We have called upon the best knights in Poland and ordered them to fight the monster,” came the reply.

That night, the king lay down upon his bed and listened in the darkness. He could hear the dragon most clearly at night-time, stoking its hot, fiery breath, like the devil kindling flames in the dark pits of hell. He could imagine it flicking out its long forked tongue and twisting its great green, scaly body, its tiny eyes as black as death, piercing the red cauldron of its den.

Late at night it would come out, prowling below the hill, plucking sheep from farmyards and cows from barns. It had grown fat on the fruits of his lands and now, like some giant war machine, was breathing fire on the forests and scorching the earth, coughing out dust and ash and cinders like a volcano, leaving it to rise and float back again to smother and choke the little city.

The king tossed and turned, and in his nightmares he saw the city buried in ash and only his little castle peeping out from the ground, a fortress under siege…

He was woken by the sound of little feet pattering up the stairs. The king got out of bed and opened the door. It was one of his smallest advisers.

“More bad news, I’m afraid, Your Majesty. Two hundred knights dead. An entire flock of sheep consumed. Another orchard burnt.”

King Krak sadly shook his head. There was only one thing left to do.

“Go out into the city and tell the citizens that the king offers a reward to any man or woman who can kill the dragon!”

“What will the reward be, Your Highness?” asked the adviser.

“Whatever they wish,” said Krak, in despair.

The man went out into the city and, running through the cobbled streets, began announcing the king’s reward among the people.

The news reached the ears of Skuba, a poor shoemaker who lived on the outskirts of the city, above a little shop with dirty windows. He had just that moment got up to mend the leaking soles of his boots, but quickly abandoned the task and began to think of a way to outwit the dragon.

He went into a back room of the shop and found an old sheep’s hide, a piece of thread and a large needle. Then he went out of the city to a quarry, where there was an abundance of sulphur, and filled several large bags.

Skuba worked through the day, splitting open the sheep’s hide, stuffing it full of the yellow sulphur crystals and stitching it up tightly with the coarse thread. This was harder work than all the pairs of shoes he had made. When it was ready, he brushed up the sheep’s white, fluffy coat so that it looked alive. He didn’t think the dragon would notice that it didn’t bleat any more. That old greedy guts would devour anything which lay in its path. It never stopped to inspect its victims – it just opened those huge cavernous jaws and gulped.

Skuba rubbed his hands. He had finished. Now to tell the king.

The king was standing in his chamber. He had turned his head to the window and was looking up at the clear blue sky and white clouds. At least something was still untouched. The king sighed. But the sky wasn’t his kingdom. His kingdom was down on Earth, and it lay in ruins all around him.

“A shoemaker is here to see you, Your Majesty. He says he can get rid of the dragon.”

Skuba, carrying the sheep under his arm, explained his plan to the king.

Krak clasped his leathery hands together and asked himself why he hadn’t thought of this before. Then, taking the sheep from the shoemaker and inspecting it, he said, “I hope it’s lifelike enough.” And under his breath he muttered to himself, “The question is, will the beast be fooled?”

Turning back to the shoemaker, he asked, “You packed it with enough sulphur?”

“I stuffed it so full, it almost burst open again, Your Highness,” the shoemaker replied.

Once the king was convinced, the hot, spicy little meal was taken down at dusk by several armoured knights and, with four sticks of wood as legs, set up near the entrance to the cave.

***

Night fell. The city slept and the king waited patiently in his castle.

“Nothing’s happening! Of all nights, it sleeps on this one – on the very night when I want it to come out and fight!”

“Sssh! I can hear something,” said the shoemaker.

Something was indeed stirring in the bowels of the castle. Steam was coming up through the floor. In a moment they both heard the sound of fiery breath and looking out of the window, they could see the night sky lit up red.

They opened the window, stretched their necks out and saw that the sheep had gone. They waited and waited… and those few seconds felt like an eternity.

Suddenly there was a great roar and the long, green, scaly tail swished outwards, clearing everything in its path, as the beast lurched towards the river. There was a loud hiss of water quenching fire, so loud it could have split the heavens, and slowly the water in the Vistula – the filthy, ash-ridden, muddy water – disappeared, and the creature’s huge body filled out, until its scaly skin was stretched tight like a balloon.

The shoemaker put his fingers in his ears and the king did the same.

“One, two, three – BANG!” they both shouted.

***

The explosion could be heard for miles. The sky was lit up as if a whole bag of fireworks had been let off. People woke, pulled rudely from their dreams, and looked out of their windows in wonder.

The news spread like wildfire. The great dragon was dead! Wise and benevolent Krak, founder of the city of Krakow, had defeated the dragon at last, with the help of a cunning shoemaker.

Peace reigned and the clear-up began. Fresh water filled the river again. The walls of houses and churches were scrubbed and the black soot removed so that the gold and turquoise of the domes and spires shone through once more. Farmers went back to their fields and repaired their fences and broken gates. Merchants started to visit the city again, bringing their wares to the great market in the main square. Wealth flowed back into the kingdom.

The king was happy and carefree once more. He patted Skuba on the back, and said, “I might have wasted my entire kingdom in an endless war with the beast, had it not been for the cleverness of this chap. Now for your reward, young man. What will it be?”

The shoemaker thought for a moment, and then said: “I’m a poor man who loves making shoes. I live on the outskirts of the city and trade is difficult. All I ask for is the dragon’s skin, so that I can make lots of pairs of shoes for the poor – for I know how it feels to walk on snow and ice in winter with bare feet.”

The king laughed.

“A modest request. I grant it – and you shall have a new shop near the castle, and, I hope, more pairs of shoes to make than there are feet in my kingdom!”

The Amber Queen

Jurata was Queen of the Baltic. Her hair was the colour of amber and her eyes were green and shone like the sea. She was a good queen and all the sea creatures loved her. Her palace, which was made from amber, lit up the sea-bed like a sparkling jewel. Throu

gh the windows she kept watch, always ready to go to the aid of those in need.

In return, all the sea creatures helped out in the palace. Sea-horses hung from the curtain rails and wiped the windows. Crabs tidied the cupboards. Cuttlefish polished the chandeliers. Lobsters weeded the garden. Sea cucumbers cleaned the baths and jellyfish hung out the washing. When a fight broke out among the crayfish, the queen was there at once, administering justice with her gentle eyes. When a sea turtle fell and broke its shell, she let the creature sleep in her bed. When a baby cod caught a cold, she wrapped it in seaweed and nursed the little fish until it was well.

One day, when Jurata was in her coral garden, a shoal of worried plaice swam up to the gate.

“Gentle queen, we need your help. A fisherman has strayed into these waters killing fish for food. Six generations of a halibut family have been wiped out. And the same has happened to a family of cod. The mackerel are fleeing for their lives and one of our friends who escaped from the fisherman’s boat told us of a terrible torture in which our cousins have been smoked to death over fires to make food for the fisherman’s friends.”

The queen of the sea shook her long amber hair.

“How dare a man from land set foot in my waters and capture my fish! You are all under my care and I will not let him harm you.”

Jurata went into her palace and began pacing up and down the corridors as she considered what to do. Her eyes glowed like fireballs, her feet stamped like thunder and up on the surface of the sea the fisherman’s little boat rocked among the waves as he sailed back to land.

At last she summoned her mermaids.

“I won’t let a man kill my fish. He must be punished. We will cast a spell upon him and draw him to us with our singing. Then we will drown him.”

She sailed out in an amber boat and the mermaids followed behind her, sitting in enormous yellow shells. They sang a lullaby so enchanting that the clouds stopped and listened and the raindrops danced as they fell.

The Dragon of Krakow

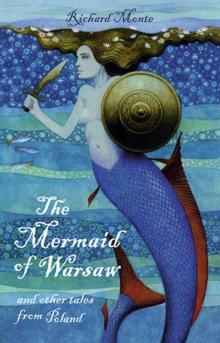

The Dragon of Krakow The Mermaid of Warsaw

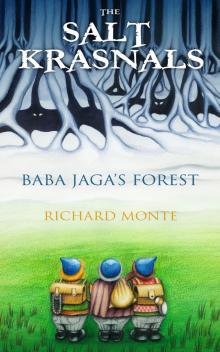

The Mermaid of Warsaw The Salt Krasnals

The Salt Krasnals